NEWSLETTER

BE FIRST IN LINE FOR OUR NEXT RELEASE.

© 2025 TIPSTER. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

NEWSLETTER

BE FIRST IN LINE FOR OUR NEXT RELEASE.

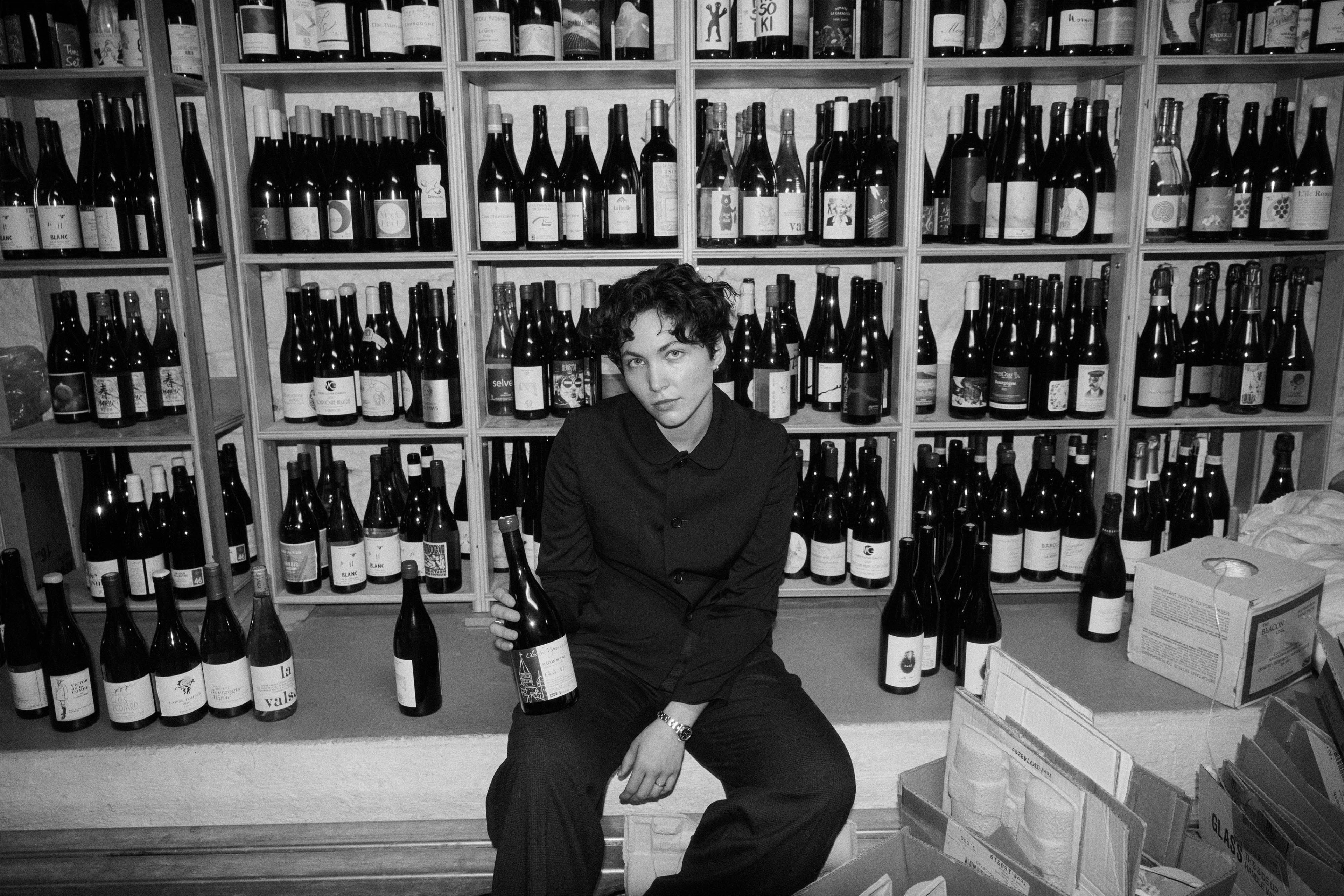

Words by Marcelo Jaimes Lukes / Photos by Sacha Maric

“I got fired from the first natural wine bar I worked at,” says Ava Trilling. The twenty seven year-old smiles at me as she recalls her ill-fated position.

“I didn’t know anything, and they made me feel like shit for it.” She doesn’t name the place, and she doesn’t need to. Anyone who’s clumsily attempted to pronounce Pouilly-Fuissé can imagine the scene.

“That’s when I told myself: one day, I’m going to open something. And no one will feel like shit there.”

Trilling’s revenge is Rude Mouth, which opened in early 2025. In the space occupied by craft beer bar Spuytin Duyvil on Metropolitan Avenue, there are no sommeliers, no maps of Grand Cru vineyard sites, and certainly no talk of terroir unless you ask. The wines lean low-intervention, but Trilling eschews any talk of dogma. Guests are poured a taste before they commit. Trilling says they then often look up with bewilderment. “After that splash, they’re like ‘Wait what do I do now?” She says with a chuckle.

“We only ask, ‘What does it make you feel?’ I don’t know if there’s much else worth asking.”

Trilling says she doesn’t want Rude Mouth to give the vibe of a New York wine bar. “I actually want it to feel like a kitchen," she says. “A really sexy kitchen.” There’s no hot food coming out of this kitchen, though. Instead, Trilling wants her team to be able to prepare the wine’s accompaniments between pours. Crisp slices of baguette are offered up with Cantabrian anchovies. Others are served with a generous spoonful of butter. Though Trilling resists the notion of "pairings," the ribbons of Comté are presented on the menu as the ideal marriage to a nutty vin jaune.

“It’s food for wine, not wine for food. ” Trilling adds.

FOR JUSTIN

Born in New York and raised partly in Montclair, New Jersey, Trilling says she’s always been drawn to the service industry. “I was one of those kids who was always playing cashier. I was obsessed with having a little shop.” At fifteen—before she was legally allowed to work—she took a job at a sushi spot, answering phones and learning the tempo of a restaurant. “I loved the operations,” she says. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, I have responsibility.’ It was thrilling.”

Then came music. “I was in a C-list band” Trilling jokes. She doubles down after I chuckle—is there such a thing? “No, really. We got signed to Sub Pop when I was, like, fifteen.” She toured, then walked away. “I actually hate performing,” she says. “By the time I was twenty I couldn’t stand it.”

What followed was a drift through wine shops, bars, restaurants—anywhere she could be around bottles and people. “I applied to The Four Horsemen when I was eighteen,” she recalls. “I never heard back.”

Years later, while working on a wine pop-up project (also named Rude Mouth) with her sister, Sophie, Trilling met up for lunch with the late Justin Chearno, the founding wine director of The Four Horsemen—one of the "horsemen" himself.

“We just sat outside and talked for hours,” she says. “There wasn’t even a job open. But I told him I loved the wine program. I said I wanted to do the same thing one day.”

By the end of lunch, Chearno had invited her to join him—not as a server, but as his right hand in the cellar. “Before I started, he asked me if I was going to copy everything he’d done when I opened my own place.” Trilling laughs. “I told him, I could never accomplish that.”

She trailed Chearno daily, nine to six. “Admin, buying, everything,” she says. “I just sponged it all up.” She stayed for nearly four years. Trilling speaks of Chearno reverently, as though he was a sort of sommelier prophet. “He wasn’t gatekeeping,” she says. “He introduced me to every relationship he had. He taught me how to run the best wine program in the world. To me, he made wine human.” On the Rude Mouth menu, a pour of Cyril Zangs’s Double Zero is labelled as an homage: For Justin.

HUMANIZING WINE

Trilling insists that despite her best efforts to follow Cheano’s lead to humanize wine, she’s fighting an uphill battle. “Wine has historically been for the rich, for the famous, for the wealthy,” she says. “Unfortunately, it often continues to be passed down that way.”

Her task, as she explains it, is to carve out a space where guests can walk in (Trilling scoffs at the suggestion of reservations!) and can be as curious as they want to.

“Some people come because it’s just a calm place to sit.” Calm indeed. Trilling enlisted a friend—a self-described rogue vintage dealer named Carlos Vescovi—to source 1970s orb lights and old Parisian café stools. Her mother's architectural lighting firm, Melanie Freundlich Lighting Design, handled the ceiling plan. A poster of Robert DeNiro in Taxi Cab greets guests as they enter.

“I guess I designed it to be a place just for me,” Trilling says, pointing out the vintage lamps from Italian designer Harvey Guizzini. “Well, me and hopefully a general manager soon.”

“We only ask, ‘What does it make you feel?’ I don’t know if there’s much else worth asking.”

While most New Yorkers her age may be getting off the L train to revel in Williamsburg’s nightlife, Trilling’s evenings are spent between the cellar and the bar floor. “I haven’t had a day off since we opened," she says. “My friends have to come here if they want to see me. I thought it would be hard. But it’s so much harder than I thought.” She laughs—briefly, and without complaint.

As our conversation evolves into a discussion of Alsatian winemakers, Trilling glances around anxiously. “We open in two hours,” she says. “I’m sorry, I have so much to do.” I promise to return for a glass and Comté ribbons. Before I go, I ask: “What do you like to have when you’re sick of wine and cheese?” Trilling doesn’t hesitate. “Well, cheese and wine.”

RUDE MOUTH

359 Metropolitan Ave,

Brooklyn, NY 11211