NEWSLETTER

BE FIRST IN LINE FOR OUR NEXT RELEASE.

© 2026 TIPSTER. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

NEWSLETTER

BE FIRST IN LINE FOR OUR NEXT RELEASE.

LIQUID DINNER FOR SCHMUCKS

Before Moe Aljaff built the Lower East Side’s newest cult cocktail spot, he was a teenage bootlegger in Sweden, a bar crawl promoter in the Netherlands, and a world champion bartender in Norway. After closing his beloved Two Schmucks in Barcelona, he’s come to New York to stay. Schmuck, on First Avenue, is the cinematic conclusion to Aljaff’s journey, a dazzling, chrome-filled hangout that earned the title 59th-best bar in the world just months after opening.

Words by Marcelo Jaimes Lukes

Photos by Sacha Maric

“I’ve been selling alcohol since I was 14,” Moe Aljaff tells me with a smirk. Before I can ask what he means, Biggie Smalls cuts through the room—loud enough that our conversation bends around it. Aljaff nods along to the beat.

It’s 4:15 on Thursday afternoon, and Schmuck is already full. As bartenders weave past space-age lamps and designer chairs in cropped Dickies shirts, pajama sets, and high-waisted pleated pants, Aljaff leans in to keep talking.

Aljaff’s own journey is one of displacement and discovery. He grew up in Västerås, east of Stockholm, after his family arrived in Sweden as refugees from Iraq. “The neighborhood that they put us in only had a few Swedish kids,” he says. “The rest were immigrant kids from all over the world.” He learned about flavors through the home kitchens of his classmates: Somali meals mixed meat with bananas, Albanian tables were always stacked with peppers prepared every which way, and Kurdish dishes showcased spices he’d never tasted before. “It was the most diverse place I’ve ever lived,” Aljaff says. “Even the one Swedish kid in my class had an immigrant accent from being around so many of us.”

After his brother went to jail for selling drugs, Aljaff left Sweden. Amsterdam was his first stop, and he got a job handing out pub-crawl flyers before working the graveyard shift at a bar-hostel hybrid. “I saw some wild shit,” he says, recalling the late nights in the Red Light District. “But I loved working at that bar, and I was always covering when people were sick so I could work more.”

Cocktails weren’t really his thing. In fact, he didn’t even touch one while in Amsterdam. “I swear I never made a single cocktail for the first five years of bartending,” he says, explaining that he manned the beer-and-a-shot type of establishments. Only in Norway, working for owners who were about to open the now-renowned Himkok cocktail bar, did he encounter mixology as both a craft and an industry.

“I didn’t know there were seminars, education, and liquor brands paid for all of it,” he says, smiling at his youthful naïveté. “I was in my early 20s and thought I knew everything there was to know about bars.”

He did know about dive bars, Aljaff concedes. “If you want to have a great dive bar, you need to have great music, great lights, and a great atmosphere,” I ask him why. “Because you can’t rely on your drinks,” he retorts as if it were a punchline.

“I’m serious. I was born for this business.” He laughs, remembering the system: he and his brother would take the ferry across the Baltic from Stockholm to Tallinn and fill a hockey bag with hundreds of plastic vodka bottles. They’d bring their smuggled liquor back to Sweden and sell it around town. “Friends, classmates, adults—everyone bought it,” Aljaff tells me, as though he were letting me in on a secret. “Our best days for business were Sundays, when the liquor stores were closed.”

The high-proof entrepreneurship was early training for Aljaff’s house party-like cocktail bar, which has quickly charmed New Yorkers since opening in February 2025. “People want to feel a part of your process,” Aljaff says. “Schmuck is about bringing you on our journey.”

DON’T CALL IT A CLASSIC

Fortunately for its guests, Schmuck’s cocktails are as much the star of the show as the atmosphere. Aljaff puts it plainly: “For us, it doesn’t start with a classic cocktail with a twist. It starts from a flavor combination, or a culinary idea.”

Liquid concepts come from travels, from inside jokes, from challenges waiting to be conquered. The Peaches and Cream, now a staple on the menu, references a gelato popular in Switzerland: an acidic frozen base topped with hand-whipped cream and a pinch of salt. The Larb Gai cocktail was built from the daiquiri-like components of the Thai dish that Aljaff ate daily while living there: toasted rice syrup, mint, cilantro distillation, lime, and chilli oil.

“It doesn’t have to be a dish,” Aljaff is quick to clarify. “Sometimes we focus on flavors, like blue cheese, banana, and coffee.” He chuckles and admits, “I just love blue cheese and coffee. So I asked ‘How do I harmoniously combine these flavors?”

Creating without classic cocktails as a starting point is “freeing,” Aljaff says. Though it also opens his team up to experimenting with drinks that don’t quite make the mark. “We’ve all had some sort of culinary cocktail that makes us ask, ‘Why the fuck did you put garlic in this, dude? That shit is fucked up.’ But the beautiful thing about our process is that there are so many ways to fix our mistakes.”

When a cocktail is about to make it onto the rotating menu, Aljaff and his team perform a simple test: take a sip, wait five minutes, and then sip again. “If you want to have another one at the end of the drink,” he says, “then it’s a great drink.”

“Schmuck is me and Juliette. We show up here at the bar, and it’s our home.”

PERSONAL BRAND

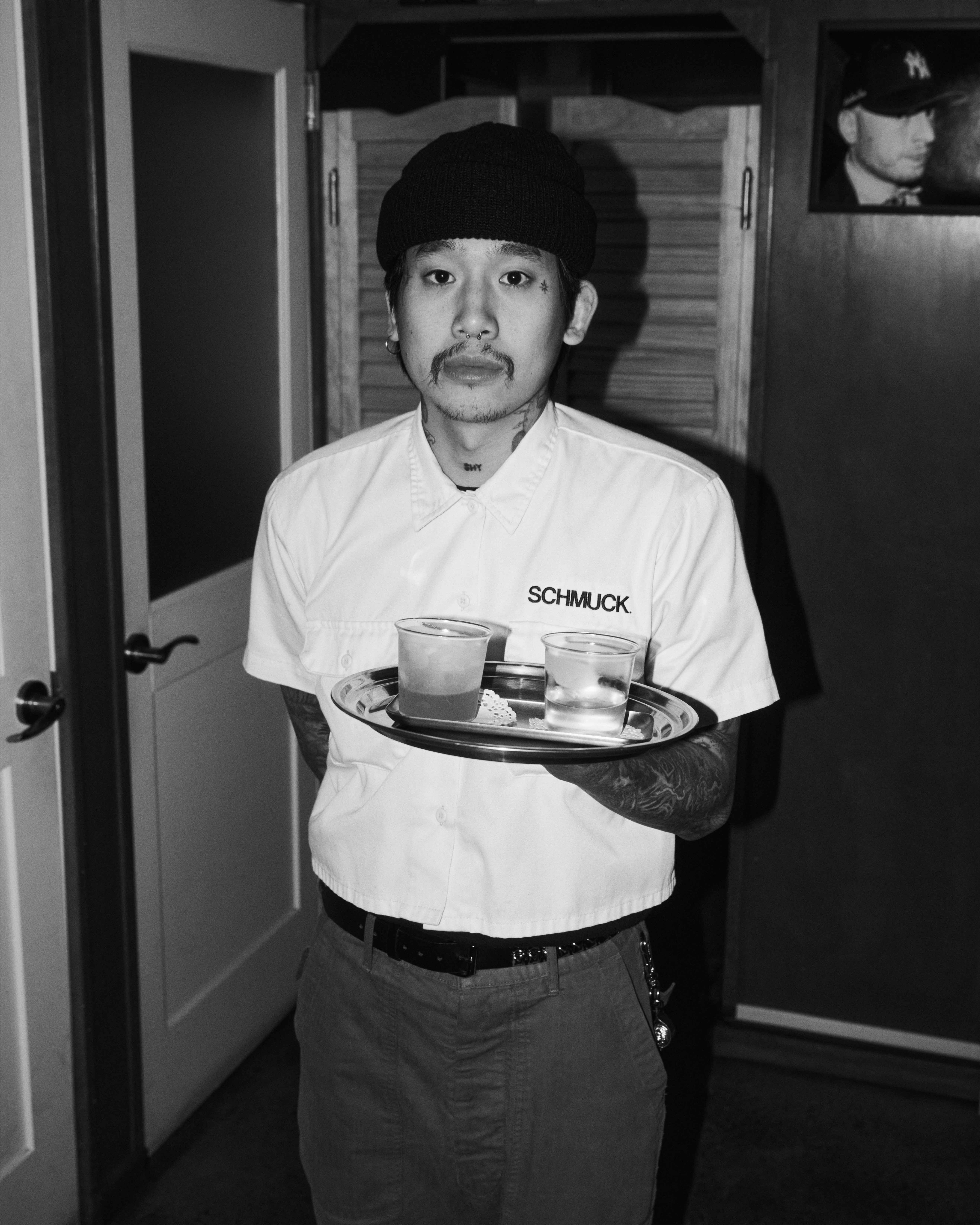

Apart from its fish-sauce-laden cocktails and bass-heavy soundtrack, Schmuck is set apart by its design. An evolution from the “punky and chaotic five-star dive bar” that came to define Two Schmucks in Barcelona, Aljaff explains that Schmuck represents his personal style, alongside that of his business partner, Juliette Larrouy.

After leaving Barcelona and beginning their project on the Lower East Side, the pair were living in short-term rentals, sleeping on couches, and finding Airbnbs that didn’t break the bank.

“We made Schmuck as our living room, because we didn’t have one.” The space is a collage of their influences. A rug on the wall by a French designer references the way homes are decorated in Iraq. A custom-made host stand by Swiss firm USM reflects the Larrouy and Aljaff’s space-age design aesthetic. Even the staff wardrobe is a thesis on personal style: multiple silhouettes, no forced matching, but unified enough to feel intentional. “We hated uniforms when we came up in bars,” he says. “So we made a whole wardrobe that allows our staff to feel comfortable being themselves.”

Schmuck’s atmosphere changes incrementally—coasters added one week, lighting swapped the next. “We’re a brand in progress,” he says. It’s a portrait of two people who have brought the energy of a dive, the elegance of a cocktail bar, and the ethos of a showroom to First Avenue.

By 5:30 p.m., the room hums with even more energy than before. Olive oil droppers and pickled beetroot highballs are flying across the angular chrome bar.

“Schmuck is me and Juliette,” says Aljaff. “We show up here at the bar, and it’s our home.”

SCHMUCK

97 1st Ave

New York, NY 10003